Cultures as a Relational World Making

“We do not see the Wind but we see the vortex it creates in a tornado”

How do we make sense of the world and our place within it? The secular ways of knowing, which prioritizes the material as the sole tangible aspect, suggests that as long as we measure, understand and in some cases possess the material, everything can make sense. I see this arising from the arrogance of coloniality. Humility brings honesty. If we are humble, we can sense the mystery through which life communicates with us. If we were humble, we would notice that life speaks beyond the things that are measurable, understandable, or ownable. If we were humble, we would recognize our humanity and the inherent fallacy in believing that the world and self and our intelligibility of them are confined within the realm of tangible thought, denied of intangible experience. We come to these alternate ways of knowing in those liminal moments, of what some would say — dreaming, where our understanding of reality breaks down because Life presents itself in ways that is unprecedented or does not fit our model of reality anymore– sometimes with ironic recurrences. My hope is that these moments give us the humility to feel the Wind.

Alexander (2005) says,

We do not see Wind, but we can see the vortex it creates in a tornado. We see its capacity to uproot things that seem to be securely grounded, such as trees; its capacity to strip down, unclothe, remove that which draws the SAP, such as leaves; its capacity to dislodge what is buried in the bowels of the earth. Wind brings sound, smells, messages that can at times be directionally deceptive so that we can be prompted to go in search of truth. Its behavior can be sudden, erratic; it can cleanse and disturb; provoke, destroy, caress and soothe. We learn about and come to know Wind by feeling, observing, perceiving, and recognizing its activity; in short, by remembering what it does as bodily experience.

What are the ways in which we come to recognize experiences beyond the secular? The modern world, with its distinctive sense of constant busyness, disconnection, and anxiety, offers ample opportunities — always moving, never arriving, an overwhelming amount of tasks, places and identities to assume. All in the name of finding security, finding belonging or finding self — living, doing, or being recognized — that inescapable rush forward! The ripples of which manifests in our internal states, relationships, and social interactions. What often remains unrecognized, behest to us, is that the existential unrest or depression we experience is not due to lack of effort or information. Instead, it is some combination of systemic forgetting and individual innocence.

There are principles to be adhered to, but there are no written maps to navigate confidently in these alternative ways of knowing and acting. To not know is to be confused, doubtful, or lack inspiration. To not be confident in action is to be unclear, unsatisfied, or stressed. What’s fundamentally missing is trust in something beyond the ego-centeric self, something that we all have a sense of but lack structures of perceiving it. Various epistemes and pedagogies refer this ‘something’ differently — as the Universal, the Beyond, the Sacred, the Spirit, among other names. If you ask me, I would say my aspiration is to a way of being and becoming where every breath reminds me of my connection with the Universal, every interaction is a collective art making and every movement is a journey to arrive.

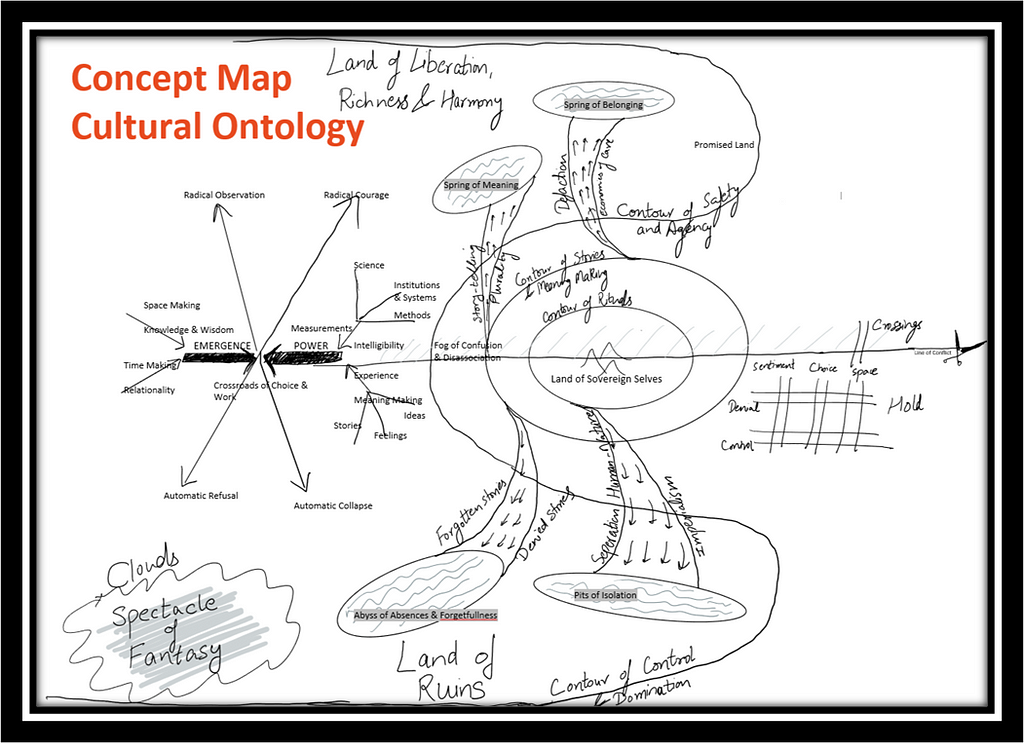

The spectacle of the mundane world is magnetic and our forgetfulness lends itself to the vividness of these experiences. Thus, I imagine a different episteme of knowing the Univeral, one that bridges the mundane and the Universal— a relationship. Bynum (1999) discusses “personalism” a concept in the African context reflecting this perspective, but for many of us not raised in those environments, it remains an alien concept. For this writing, I orient us towards the concept of “Cultures” as an intermediary between the mundane and that embodied knowing of the Universal — a more familiar and accessible concept. I present a map which contours “Culture”, highlighting enduring structures of Old, colonialism and meta-colonialism, that keeps us in this fog of forgetfulness, and explore new lands as a radical departure from these Old ways towards richness, harmony, and beauty. The key questions addressed are, “How do we know “Culture” as this mediator?”, “Why do we forgot our “Culture” as this mediator?”, and “What choices do we, as individuals, have in this context?”.

What are the ways we can know Culture?

The roots of the world Culture can be traced back to mid 15the century which comes from the Latin root “Cultus’ — which means “the act of care or promoting growth” (Berger 2000). It was primarily used in the context of plants through tending to the soil and the crop. Culture in the modern sense is used more broadly. Anthropologically it is defined as: “A concept that encompasses the shared patterns of behaviors, beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, values, and material objects that members of a society use to cope with their world and with one another. These shared patterns are learned and transmitted from generation to generation through various means, including language, rituals, and daily practices. Culture shapes the way individuals perceive, react to, and interact with their environment and with other people.”

Culture profoundly shapes individual identity and community belonging. It is a key factor in how people understand their identity, providing a sense of where they belong in the world. This understanding is crucial for personal development and self-awareness. Culture also fosters a sense of community, linking individuals to a larger group with shared beliefs and values, offering comfort and cohesion, especially during change or stress. Additionally, culture is essential for effective communication within a community, as it provides the necessary tools and context for social interaction, guiding relationships and social structures (such as families, communities, etc.). On a broader level, culture is the lifeblood of a vibrant society, offering a sense of delight and wonder to individuals. It provides a feeling of place and interconnection, contributing to psychological well-being by offering stability and a buffer against life’s stresses. Cultures hold parts of the psyche that are challenging to interact with directly, revitalizing daily life through continuous reorientation. They form the relational fabric of human experience, creating vibrant economies and societies by offering guidelines for all aspects of life, thus reducing internal conflicts.

Dagmang (2020) highlights that culture is prominent when local interactions are shaped by shared beliefs and traditions. In simpler societies, such as the indigenous Mandaya tribe of Southern Philippines, there’s a congruence between economic practices and cultural traditions. In such contexts, the idea of reciprocity informs exchange practices, contrasting with the strictly rationalized transactions of urban capitalist settings. While small-scale commercial activities may integrate into traditional trading patterns, problems arise when capitalist rationalization suppresses cultural expectations of care or solidarity. This illustrates how culture can provide a local interpretation of broader economic practices, underlining the significance of maintaining cultural identity in the face of global economic pressures.

It is also crucial to recognize that when social spheres overpower individual self-perception, the same cultures that offer us a sense of place, belonging, and purpose can be manipulated by the social hegemony. In such scenarios, cultural rituals, meaning-making, and modes of identity formation can become tools for suppressing individual expression, choice, and autonomy. Therefore, it’s important to center relationality where both the individual and culture meet without one dominating the other.

In these ways knowing cultures reminds us of the knowing the Universal, our collective existence, of Sacred in our daily lives— in our relationship with ourselves, with others, our families, communities, nature, non-human others, and the wider collective. These interactions are perceived as mirrors of the relationship between the material and the universal. Alexander (2005) writes, “All the mundane activities of working, eating, sleeping, having sex, and getting sick and getting well are forms of body praxis and expressive of dynamic social, cultural and political relations”. I offer a thesis that all such activities when done through a cultural lens become forms of body praxis and expression of the dynamic energy of the Universal. This leads to a critical question: While we connect with a sense of cultures in these ways, why do we not remember our own cultures, why do structures of knowing our own culture escape us?

Why did we forget our Culture?

Dagmang (2020) elaborates on how state-management practices and capitalist cultures can subordinate traditional societal practices, transforming societies into centers of production and consumption. The dominance of a capitalist culture, characterized by private ownership and profit-making, overshadows communal traditions of care and relationality, reshaping individual and societal values. This transformation, driven by utilitarian reasoning, also extends to political power, which increasingly uses knowledge and information to normalize social relations. An example of this is seen in the strict application of formal requirements in commercial transactions, which can override human compassion and community values. This underscores the tension between traditional cultural values and the demands of a capitalist society, highlighting the need to preserve cultural identity and relational practices in the face of overarching economic systems.

Cultural knowledge and practices, traditionally transmitted through rituals, storytelling, and education, face erosion under the influence of a colonized history that favors Eurocentric perspectives and diminishes the value of colonized cultures, as highlighted by Bulhan (2015). This process alters indigenous religions, knowledge, and identities, leading to a distorted blend of history marked by mythology, selective recall, and interpretation, especially under oppressive conditions. Metacolonialism exacerbates this distortion, glorifying Euro-centric hegemony and reshaping reality for the colonized. The imposition of the colonizer’s language further erodes cultural identity, creating a dynamic where fluency in this language equates to social status, marginalizing indigenous languages and practices, and leading to cultural homogenization. This identity colonization not only internalizes feelings of inferiority among the colonized but also displaces indigenous customs, profoundly disconnecting people from their ancestral identities and reshaping both personal and collective histories.

Metacolonialism profoundly affects the social context of cultural learning, as economic forces and colonial ideologies penetrate homes, disconnecting cultural identity from contemporary realities and creating a conflict between traditional needs and modern desires. This conflict is further intensified by a Eurocentric, Newtonian interpretation of time, which emphasizes productivity and profit, overshadowing traditional cultural values. The push towards Western assimilation often undermines the religious heritage and cultural identities of non-European peoples, contributing to cultural erosion. Metacolonialism’s primary aim is to dominate the colonized in all aspects — economically, culturally, socially, and psychologically — with well-being measured by materialistic standards, reinforcing power and wealth disparities. This materialism, combined with a psychology that promotes individualism over collective well-being, neglects the essential social nature of human beings. The resulting imbalance overlooks the importance of collective well-being and liberty, crucial for a meaningful existence. The pervasive control exerted by colonial powers over all aspects of life, including economy, politics, culture, and knowledge, not only complicates the path to liberation but also contributes to the gradual erosion and forgetting of indigenous cultures, as traditional knowledge and practices are devalued or suppressed in favor of dominant colonial narratives.

Coloniality creates divisions, setting culture against nature, and people against one another, while reinforcing practices that uphold hegemony. Battle lines are drawn between all that is true, useful and valuable within the pluriversal world and the hegemonic system. Individuals often find themselves caught in the middle of these conflict zones. Ferdinand (2022) brings in the concept of the “politics of hold,” referring to also the psychological colonization akin to the confinements of a ship’s hold, symbolizing the state of the psyche under metacolonialism. Assault of all these forces of colonization creates a fog of confusion, doubt and psychosis on an individual. The individual then becomes a tool for the hegemony forgetting its own self, forgetting its own culture — one of many.

What choices do we have? — Lay of the Land: Cultural Ontology

Figure 1 attempts to map out the contours and territories of this battleground. Alexander (2005) writes, “To oppose freedom to violence is to sharpen the fault line where democracy butts up against empire. It begs also for new definitions of both freedom and democracy. What is democracy to mean when its association with the perils of empire has rendered it so thoroughly corrupt that it seems disingenuous and perilous even to deploy the term. Freedom is a similar hegemonic term, especially when associated with the imperial freedom to abrogate the self-determination of a people. How do we move from the boundaries of war to the edge of each other’s battles? How many enemies can we internalize and still expect to remain whole? And while dispossession and betrayal provide powerful grounds from which to stage political mobilizations, they are not sufficiently expansive to the task of becoming more fully human… The terms of this new contract will have to be divined through appropriate ceremonies of reconciliation that are premised within a solidarity that is fundamentally intersubjective: any dis-ease of one is a disease of the collectivity; any alienation from self is alienation from the collectivity. It would need to be a solidarity that plots a course toward collective self-determination. Among its markers will be the knowledge that all things move within our being in constant half embrace: the desired and the dreaded; the repugnant and the cherished; the pursued and that which [we] would escape. It will entail the desire to forge structures of engagement, which embrace that fragile, delicate undertaking” of relational emergence (see Maree 2017).

Communities develop within their unique local bioregional environments, forming ecologies of knowledge that are shaped by the elements they emphasize in their worldview. In this landscape Figure 1 centers individuals who find themselves at a crossroads between hegemonic systems and structures (the Old way) and the liberating whispers of the Wind, which inspire self-creativity and fuel the Fire of new possibilities (the New way). Liberation and self-creativity are not individual concepts; they cannot thrive in isolation. My own liberation is inextricably linked to the freedom of those around me, as true creativity is inherently a collaborative process. This collaboration can be direct or understood in a more mythical sense, recognizing that creation requires an observer. Bulhan (2020) observes, the individualistic focus of capitalism often overlooks the importance of collective well-being. True liberation and creativity requires a meeting of individual and collective well-being. This balance ensures that individual differences gain significance only when the collective thrives, and the study of individuals must aim to enhance collective well-being while mitigating its potential tyranny over individual liberty. Recognizing that the colonized have choices is a powerful affirmation of their potential to transcend and reshape their circumstances.

Harney, et al. (2012) writes about “Hapticality”, a way for successful departure from the “Hold” — “the capacity to feel though others, for others to feel through you, for you to feel them feeling you, this feel of the shipped is not regulated, at least not successfully, by a state, a religion, a people, an empire, a piece of land, a totem. […] Thrown together touching each other we were denied all sentiment, denied all the things that were supposed to produce sentiment, family, nation, language, religion, place, home. Though forced to touch and be touched, to sense and be sensed in that space of no space, though refused sentiment, history and home, we feel (for) each other.” Apffel-Marglin (2020) offers us the concept of Agencement to help us understand this as a way of co-creating commons with “Earth-others.”

These are the ways in which pathways of transition can be forged. When we individually and collectively feel — feel though others, allow others to feel through us, and allow us to feel them feeling us; when we individually and collectively dream and imagine liberation and emancipatory realities; and when we individually and collectively believe, affirm and demand we build cultures of successful defection and departures from colonized realities towards spaces of safety, harmony and richness. Maldonado-Torres (2016) offers a thesis that explores the multiple layers involved in these creations of coloniality and the ongoing resistance against it. Statement of the World Peoples’ (2015) is another text which offers alternative proposals for “defense of life”.

When we can feel, imagine, and demand then we step into place & time making, an emergence of being. When we reclaim and reaffirm our stories and experiences and organize & ritualize epistemic and institutional systems (for example, Lansing 1987 — Balinese Water Temples) we become to consolidate power. In that meeting point we arrive at a fork on the road.

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood…

and I —

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.” - Robert Frost

And choice present themselves, and a choice has to be made. Would that choice be a choice of relationality — a radical observation and radical courage to take the path less traveled, or would that be an automatic choice of refusal and collapse where we become instruments of colonizers, labor resource for capitalists, and continue propagating what our hearts want to move beyond? This is the spirit in which I offer this article.

Cultural Symbolisms and The Universal

References:

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2016). Outline of Ten Theses on Coloniality and Decoloniality.

Bulhan, H. (2015). Stages of Colonialism in Africa: From Occupation of Land to Occupation of Being

Apffel-Marglin, F. (2020). Co-Creating Commons with Earth Others: Decolonizing the Mastery of Nature.

Statement of the World Peoples’ Conference on Climate Change and the Defense of Life, (2015) Tiquipaya, Bolivia

Alexander, J. (2005). Pedagogies of the Sacred: Making the Invisible Tangible

Bynum, E. (1999). The African Unconscious (pp. 77–102)

Watkins, M. and Shulman, H. (2007). Toward Psychologies of Liberation

Maree Brown, A. (2017). Emergent strategy

Ferdinand, M. (2022). Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World

Berger, A. A. (2000). The Meanings of Culture: Culture: Its Many Meanings. M/C Journal, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1833

Dagmang, F. D. (2020). Society and Culture: Matrix and Schema for Character Formation.

Harney, S., & Moten, F. (2013). The undercommons: Fugitive planning and black study.

Lansing, J. S. (1987). Balinese “water temples” and the management of irrigation. American anthropologist, 89(2), 326–341